Where we take a stand.

Change starts with us. These campaigns are where communities stand tall, challenge overreach, and fight for a fair go. Join us, add your voice, and help shape Australia’s future.

Our Campaigns.

Australia is at a crossroads. Too often, laws are rushed through without debate, rights are eroded without notice, and the voices of everyday Australians are sidelined. That’s why Stand Up Now runs people-powered campaigns; built on mateship, fairness, and accountability, to defend our freedoms and strengthen our democracy.

Here you’ll find our current campaigns, along with those we’ve fought before. Each campaign is a chance for Australians to step up, stay informed, and make a difference.

Active Campaigns

Censored at 16: Stop the U16 Social Media Ban

A rushed law forcing every Australian into ID checks and facial scans. We’re standing up for children’s rights, family privacy, and digital freedom

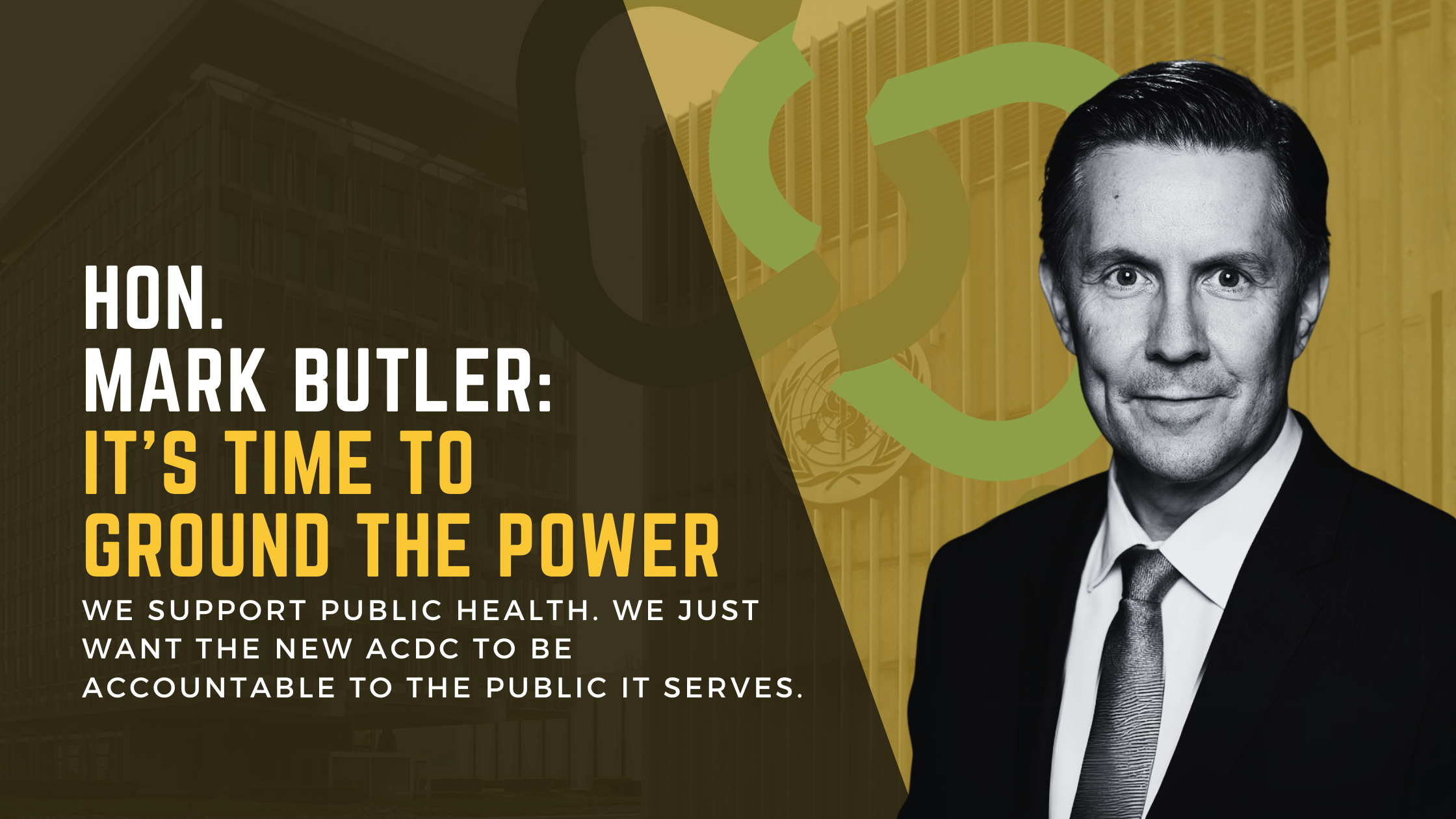

ACDC: We’re on a Highway to Hell-th

A rushed law forcing every Australian into ID checks and facial scans. We’re standing up for children’s rights, family privacy, and digital freedom

Why we campaign

Campaigns are how Australians make their voices heard. Every petition signed, every flyer shared, every neighbour convinced — it all adds up. When enough of us stand up, government has no choice but to listen.

At the heart of it all

We don’t run campaigns for headlines. We run them because families, neighbours, and communities deserve a fair go. When you chip in — with your name, your time, or your support — you’re helping keep democracy alive.